Spindlestone Limekiln

Limekilns of the North Northumberland Coast

Introduction

As part of the Peregrini Project, with volunteers, the Archaeological Practice re-examined the surviving limekilns in the area. This account, based on a more detailed report produced by Richard Carlton and A. Williams, Limekilns of the Peregrini Coast – R Carlton & A Williams provides a context for lime use in the area, explains how the kilns were used and describes the surviving remains in the Spindlestone, Budle and Outchester area.

Early uses of Limestone

Limestone is found along much of the coast, where it has been exposed by the sea. It has been used for lime-burning since at least mediaeval times, when the resulting lime was used for mortar in stone buildings. A late 15th or early 16th century lime kiln, excavated in 1995, lies on Beadnell Point, to the east of the harbour kilns. The use of limekilns is also mentioned in the mediaeval records of Lindisfarne Priory.

From the early 17th century, lime was spread on fields to produce increased yields on arable land, and richer pastures for livestock. This had become widespread by the mid-18th century. Estates had their own kilns supplying their tenant farmers, while even some individual farms such as Glororum, on the Spindlestone Estate, with both coal and lime available on the land, had its own kiln. During the 19th century, as demand for lime outgrew the capacity of field kilns, larger-scale kilns were built further afield, close to fuel and lime supplies.

Burning and using lime

A description of the working of the Northumberland limekilns is contained in Bailey and Culley’s 1797 General View of the State of Agriculture:

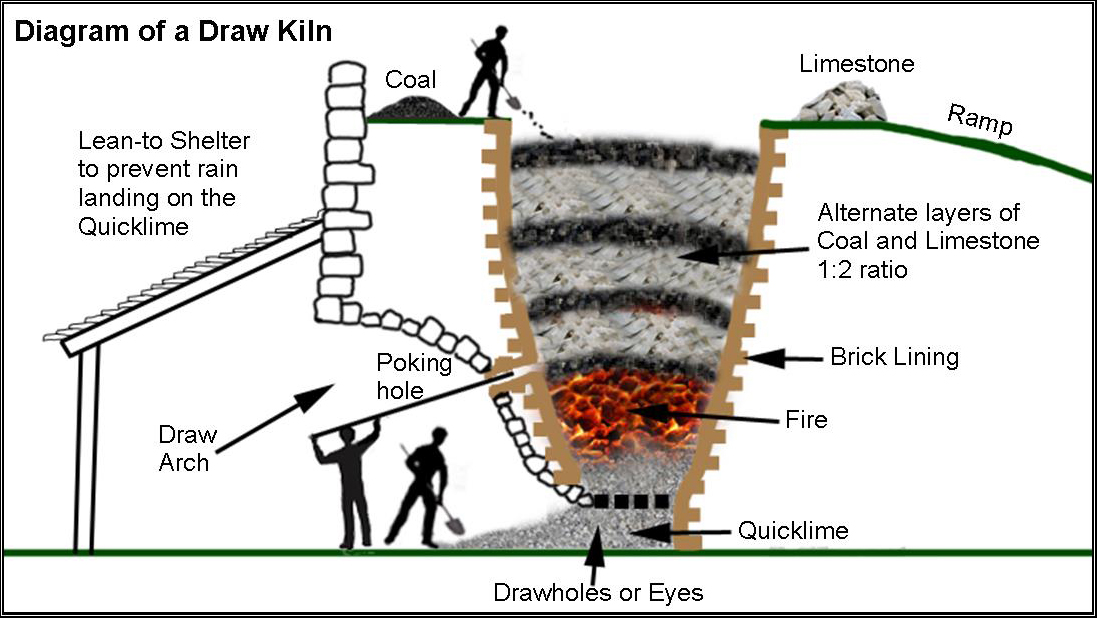

The mode of burning lime in this county, is mostly in draw-kilns, of the form of an inverted cone, with two or three eyes or mouths for drawing out the lime, and admitting air: These kilns are kept burning and drawing perpetually. Some of the large scale kilns will afford 40 or 50 cart loads a day: A cart load of coal is reckoned to burn two cart loads of lime

The principle behind the process is that under heat, carbon dioxide gas is driven out of the limestone, leaving calcium oxide, or quicklime. When the quicklime was removed from the kiln, it could be changed to ‘slaked’ lime by mixing with water. If sufficient water was added, this formed a paste, ready to be used in mortar. If the addition of water were controlled carefully enough, the quicklime would create a powder (a dry hydrate), ideal for direct application on agricultural land.

Freestanding kilns had a ramp to take the coal and limestone to the top of the pot. These were packed into the kiln in layers, often at a ratio of 1:2, and a fire kindled with wood stacked at the base. This ignited the bottom layer of coal which burnt through, heating the layer of limestone above with the draught drawing the fire through and eventually lighting the layer of coal above. Experience was needed to achieve a successful burn, regulating the heat by the opening or closing of the draw holes or eyes at the base of the kiln.

The surviving draw kilns are stone-built, often square or oblong in plan, widening towards the bottom, but usually partially submerged in a sea of accumulated kiln waste, sometimes built into a hillside. The smaller kilns have a single pot, tapering, funnel-like, towards the bottom. Pots are lined with stone or brick to protect their surfaces from heat erosion and thermal shock. Two, three or four draw arches, usually stone-built but sometimes brick-lined, define recesses around the openings, or ‘eyes’. These, with the draw arches, regulated the necessary draught, as well as yielding the burnt lime, which fell to the bottom of the kiln continuously once the kiln was in full operation. Above the eye there may be a poking hole, through which an iron poker was pushed to riddle the burning lime.

Identified Draw Kilns

The following Kilns were identified from existing records and visited.

Easington Grange Mill Limekiln, NU 11928 36452

This is shown on the 1st edition Ordnance Survey plan (1860) on the eastern edge of the road running north from Easington Grange Mill. No evidence for it survives today on the ground.

Easington Demesne Limekiln ‘A’, NU 11966 35463

This kiln, in the north-east corner of an extensive quarry shown on the 1st edition Ordnance Survey plan, is now very fragmentary and obscured by rubble and soil build-up around it. One pot is visible, circular in plan and with a firebrick lining, with three, possibly four access arches partially infilled. This kiln, along with another to the south (see below), was in use in 1860 but marked as ‘Old’ by 1898.

Easington Demesne Limekiln ‘B’, Easington; NU 12014 35331

This sits at the south-western edge of the quarry noted above and is a substantially intact kiln with multangular frontage wall of uncoursed sandstone, pierced by three access arches which are round headed with stone voussoirs. There is a ponded area against the north-east frontage of the kiln, which has one pot with a vitrified lining. An earth loading-ramp curves up from the south of the kiln.

Budle (Kiln Point) Limekiln; NU 1537 3534; HER 5093

This kiln lies to the east of a lane running down to the shoreline at Kiln Point on Budle Bay. It is in a fairly poor condition with one of the three access arches having collapsed. It has a multangular frontage wall of random whin rubble facing south with (originally) three round-headed access arches with brick voussoirs and a wing wall to the east. There is one central pot, circular in plan but infilled. A tightly curving earth loading ramp runs from adjacent to the trackway and up to the loading platform. The kiln was in use in 1860, when a track is shown on the 1st edition Ordnance Survey plan running from the lane south of the kiln to the shoreline, but was disused by 1898. Structures shown on the east face of the kiln, and to the south, are not obvious today.

Spindlestone Limekiln, NU 1521 3362

This is a large rectilinear structure of coursed sandstone rubble with neatly cut angle quoins at the north end and with massive clasping buttresses added below the kiln which is built into a gentle slope climbing to the south. Three round-headed arches, all at the north end of the kiln in the north, west and east faces, have neatly cut sandstone voussoirs and access one central pot, lined with firebricks but largely infilled The draw holes are narrow and round-headed with small, square poking holes above. As the kiln is set into a slope, the earth ramp at the south end is fairly short but extends the width of the structure. The 1st edition Ordnance Survey plan shows the kiln in use but it was out of use by the 2nd edition of 1898.

Spindlestone Draw Arch showing Poking Hole and Eye

No Comments

Add a comment about this page