Lindisfarne has been subject to the intensive attention of archaeologists since the later nineteenth century, revealing a rich range of sites and artefacts attesting to settlement and other activity from early prehistory through to recent times. It is most well-known, however, for its early medieval monastery, founded by St Aidan for King Oswald in AD 635.

The links with St Cuthbert, abbot in the late 600s, and the Lindisfarne Gospels, produced there in the early 700s are particularly well known. However, very little is securely known about the actual form of the early medieval monastery, though it is assumed to have occupied the same site as the medieval priory, founded in, or shortly before, AD 1122, the remains of which survive. Little is known for sure of the form of the early medieval establishment, but some authorities have speculated that some slight, earthwork remains on the Heugh may have been part of it.

The Tower.

One of these sites, enclosing the current war memorial towards the west end of the ridge and known only from geophysical survey, was explored in June 2016 and found to be the foundations of a massive, 2.5 m wide wall constructed of roughly cut facing stones either side of closely-packed, deeply-set cobbles, with smaller cobbles forming an upper surface. There were no significant finds to provide evidence for dating, but the massive walls and form of this structure suggests that it may have been a tower, while its absence from early maps and the lack of mortar in the structure or from the area around it indicates that it is likely to be an ancient structure. Further excavation in 2017 uncovered the south-east corner of this structure.

A Chapel.

A second site explored in June 2016 a little further to the east, in the area between the current lookout tower and shipping beacon, revealed more building foundations. Further excavation of the same site in 2017 revealed an outline structure comprising a large western chamber and much shorter and rather narrower eastern chamber. Some key dimensions of the structure taken as it was revealed are as follows:

Total external length the building from west to east along the south wall: 17.15 m

Total external length of the building from west to east along the north wall: 17.20

Internal length of West Chamber from SW to SE corner: 10.95 m

Internal length of West Chamber from NW to NE corner: 10.65 m

Internal width of West Chamber at west end: 4.65 m

Internal width of West Chamber at centre: 4.2 m

Internal length of East Chamber from NW to NE corner: 3.1 m

Other than structural remains and fragmentary facing stones, a number of worked stones provisionally interpreted as from architectural features such as windows were encountered and recorded. These were generally very crudely dressed, suggesting that they were not intended to be seen, either because they were plastered – although no evidence for use of plaster was found on the site – or obscured in some other way, such as by stone ‘shuttering’, as at St Paul’s, Jarrow. Part of a small stone trough of a kind that could have equally served a domestic or ecclesiastical function, as a piscina for example.

Aerial photograph of the remains of the Chapel. 2017.

Other finds from the excavation mainly comprised metalwork and other finds of modern origin, suggesting that the site has been used for burning and other kinds of refuse disposal over recent centuries. However, amongst a small number of finds of more ancient origin were a spindle whorl, lead ‘pin’ and fragments of medieval pottery.

Although currently lacking corroboratory arte-factual, environmental or documentary evidence, the form and alignment of the excavated structure suggests that it is a church, or chapel of early origin. Its earliest potential origins lie in the early 7th century when the monastery of Lindisfarne was established by at the behest of the Northumbrian king, Oswald, whose principal seat was probably Bamburgh, while it can not have been established later than the 11th century, when its presence would have been noted in surviving documents.

Chapel remains viewed from the east.

Several factors, including its position on a heugh within clear view of Bamburgh, point to this as a site of very early origin, although the remains uncovered in 2017 need not necessarily be those of the earliest building on the site. Indeed, early documentary sources do not appear to support the building of an early stone church, since only wooden buildings are mentioned in the context of 7th century Lindisfarne. Other factors, such as parallels with Monkseaton, Jarrow and, particularly, Escomb suggest a possible later 7th or early 8th century origin, but it is quite possible that its origins lie even later, perhaps even following the return of a monastic community following its migration in the face of Viking raids in the mid-9th century. It is hoped that the provision of dates from organic remains found on the site will soon enhance current interpretations of its origins.

The Lantern Chapel.

The final site on the Heugh investigated in 2017 is the ruined building near its west end, immediately to the west of the Coastguard Station, known as the Lantern Chapel, long thought to be the remains of a look-out or lighthouse rather than the ecclesiastical building suggested by its name. This building was recorded as a standing structure by Peter Ryder, who has commented on reused moulded stones of medieval origin built into its fabric and investigated it for its archaeological potential during the Heugh excavations of June 2017.

Excavation against the inside of the east wall revealed the mortared footings of a substantial, 0.8 m wide east-west wall. The area on its south side was not investigated due to the perceived risk of destabilising the south wall, but on the north side bedrock was encountered at a depth of 0.5 m, within which was cut a deep void containing disarticulated bone, mostly of human origin. Analysis in situ by forensic anthropologist and osteologist, Sanita Nezirovic who identified representatives of up to seven individuals amongst the human bone assemblage.

Further interpretation of the structural and archaeological remains is pending, along with palaeo-environmental sampling, but it seems clear that the current structural remains, while not themselves of ancient origin, mark the site of a chapel represented by the buried east-west wall and disturbed burials. It may be noted that, on a military map of 1548, the only building shown on the west part of the Heugh is a rectangular structure with west tower in the current position of the Lantern Chapel.

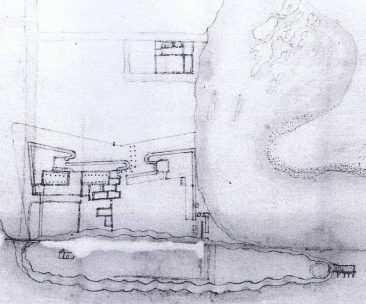

Plan dated 1548 showing a building on the western end of the Heugh.

It must be assumed that the remains uncovered in 2017 relate to this chapel. Furthermore, several large stones exposed in the footpath to the west of the upstanding building and a slit mound extending to the south of them may indicate the line of its original west wall, but further excavation would be needed to test this.

No Comments

Add a comment about this page