Looking across the peaceful landscape of Lindisfarne it is perhaps hard for the 21st Century visitor to imagine that in mid-Victorian days this Holy Island was the location of a thriving lime industry. However walks around the island reveal its remains: quarries, kilns, piles of lime and the remains of tramways.

The Middle Ages.

Lime was traditionally used for the manufacture of lime mortar, for lime washes on the outside of buildings, for ‘sweetening’ acid soils and for other agricultural and industrial purposes. It was first quarried on Lindisfarne, by monks from the Priory, as far distant in time as the Middle Ages. In the 1790s small quantities of unprocessed limestone was being shipped from the quarry on the north of the island down to North Shields.

When roasted at a temperature of over 1,000 degrees limestone decomposes and turns into quicklime. When water is added to this much heat is given off and slaked lime is formed. An energy source, usually coal, and a supply of water are thus needed for the overall process.

No traces of an early, pre-Victorian, limekiln on The Snook, at the far western end of Lindisfarne, exist today. However remains of the three Victorian limeworks are easy to see: the Lower Kennedy limeworks and the St. Cuthbert’s limeworks at The Links, plus the well-preserved Castle Point limeworks to the east of Lindisfarne Castle.

The Kennedy Kilns

It was in 1839 that the ‘Lord of the Manor’, Mr. J. Donaldson Selby applied to the Crown Commissioners for permission to erect a kiln and a jetty for shipping the lime. In 1842 Selby was given the go-ahead for these, at his own expense. In August 1845 a Berwick newspaper reported on the building of a tramway to serve the kiln at Lower Kennedy works and in 1846 Selby granted a Lease to a local partnership, Mr. David Gibson, of Belford, and John Lumsden, of Mousen, to quarry and roast limestone. In the same year another local newspaper predicted that Holy Island would become, as a result of this industry, ‘…one of the most flourishing, bustling and thriving seaports in the United Kingdom…’! Yet the 1851 census indicated that just seven men were involved in the Holy Island lime industry! At this time the source of the limestone was the outcrops of the stone on the beach near to Buck Skerrs. A tramway was constructed to lead the lime to the works at Lower Kennedy, where there were two kilns, a slaking floor and several sidings. A further line of rails led the slaked lime to a jetty at ‘The Basin’ to the south of Chare Ends. However by the mid-1850s an Inspector’s Valuation and Report’ to the Office of Woods, Forests and Land Revenues, read that there was ‘…so much competition with other proprietors on the coast that the trade is very limited.’ Gibson’s 10 year lease of the site was not renewed.

Castle Point Kilns

However around the same time an entrepreneur, William Nicoll of Dundee, negotiated an Agreement with Selby. Nicoll was a lime, coal and brick merchant of some standing. With some alacrity Nicoll built a tramway from the Nessend Quarry in the north of the island to a new limeworks, often called St. Cuthbert’s limeworks, linking this with the former tramway to the jetty for the shipping of the processed lime. However the kilns were built at a location not approved by Selby. They were abandoned after just three years. Nicoll then proceeded to relocate his works to the east of Castle Point. The original tramways were abandoned and new lines were created along the east coast of the island. One line brought the limestone from Nessend Quarry to the new kilns, another facilitated the movement of coal from the a new ‘Lime Jetty’ projecting into the Harbour, to the west of the Castle Mound, to the kilns, whilst a third linked the kilns and slaking yard to the jetty for movement of the roasted and slaked lime to the boats for shipping to Dundee. These tramways were more substantially built than the earlier ones as the surviving embankments indicate.

The Heyday

Nicoll established a ‘triangular’ shipping route: Coal arrived at Lindisfarne from pits in the south of Northumberland, lime was shipped from Lindisfarne to Dundee, and ‘general goods’ including wheat, rope and bricks left Dundee for the south of Northumberland. A variety of boats was employed in this trade: brigs, schooners, and sloops, varying in size from Nicoll’s brig, Isabella, of 302 tons, down to his sloop, Robert Hood, of just 35 tons. Over ten of Nicoll’s vessels were involved in the trade, plus other chartered vessels including the Curlew owned by Ralph Wilson of Holy Island.

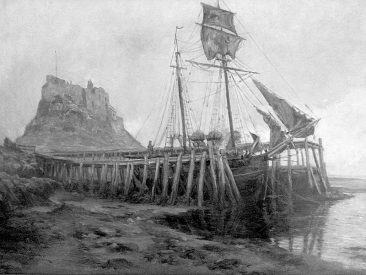

Lindisfarne Jetty by Ralph Hedley.

Copyright Fred Hoult.

From just seven men associated with winning and burning the lime in 1851 the number reached its zenith around 1861 when about 33 men were involved, plus, of course, necessary other workers such as blacksmiths. The progress of Nicoll’s concern can be judged in that by the 1871 census the number had fallen to 22. In 1881 Nicoll’s former ‘Master Limeburner’, a certain Robert M. Smith, described himself as a ‘Farmer and Limeburner employing 21 men and three boys. Only five of these appeared to be working in the lime industry, however. The quarrymen were not local men; the majority were Scots (bringing such surnames as Murray, McDonald and Wishart to the island), whilst, especially later, others brought the surnames McCredy, Nairy, Kilkenny and Dowey from Ireland to Lindisfarne. Some of these immigrants remained on the island after the cessation of the lime industry, marrying local women and bringing some much-needed variation to the gene pool! The impact of the lime industry can be judged from the changes in population numbers. In 1841 the island’s population was 497. By 1851 it had risen to 553 and then further to 614 in 1861, remaining close to this figure until 1881. By 1891 it had fallen back to just 444. By 1961 the population had declined to just 190.

The End of Lime Burning

It was in 1884 that Nicoll shipped out the remainder of his plant back to Dundee and the limestone industry on Lindisfarne ceased. Sporadic firing of the kilns took place over the ensuing 20 or so years for the benefit of the local farmers. Some of Nicoll’s vessels continued to call at Holy Island, often to take shelter from storms, when en route from Dundee to Shields or Newcastle with cargoes of wheat.

Whilst it was generally the case that horses were used to move the wagons of coal and lime, there is the likelihood that for a brief period a steam locomotive worked on Lindisfarne. A Coastguard’s Report of 1867 referred to the limestone being conveyed by a steam engine. Then, in the 1990s a very elderly gentleman told the then Holy Island postmaster that his grandfather had driven a steam locomotive on the island, but that it had not been successful and had fallen off the rails. It was, apparently, soon taken away!

Comments about this page

A good, informative read. It’d be improved if you could provide a rough sketch map of the locations of the kilns and other associated works.

Add a comment about this page